The U.S. government may be taking a few steps back on policy related to climate change, but the nation’s corporate base is still diversifying its energy mix. While only 5 percent of Fortune 500 companies had clean energy targets in 2014, 48 percent had them by April 2017, according to a report spearheaded by the World Wildlife Fund.

Advanced Energy Economy, a national business association, found that 71 of the Fortune 100 companies had renewable energy or sustainability targets in 2016.

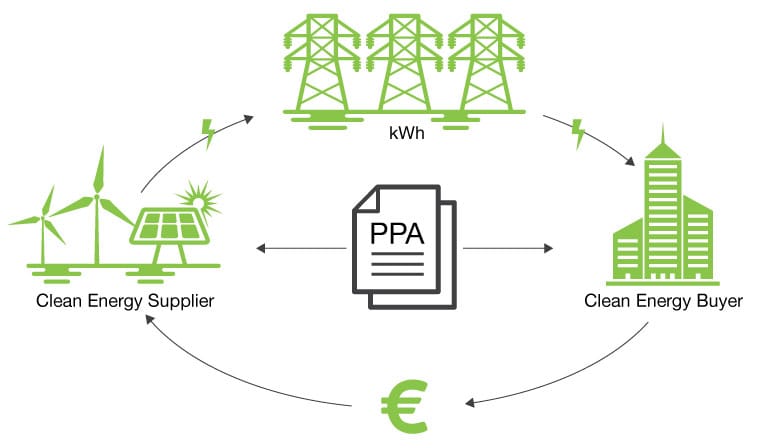

How are they meeting those targets? Many are turning to power purchase agreements (PPAs) for renewable energy. Often, these agreements involve independent solar or wind-power developers, which means PPAs have the potential to impact utility revenue and distribution systems.

The way out

The way out

Under some PPAs, a developer manages the design, permitting, financing and installation of a renewable energy system, and the customer buys electricity at a prearranged cost under a long-term contract that can act as a hedge against inflation. Initially, these generation facilities were cited on customer premises, but researchers at the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL) have found that off-site PPAs are now on the rise.

Recently, an NREL team published a September 2017 report titled Charting the Emergence of Corporate Procurement of Utility-Scale PV. In it, the report’s authors explain that physical PPAs involve a long-term contract in which solar generation is delivered to the customer by an energy supplier, while virtual or financial PPAs are contracts in which the buyer pays for but doesn’t receive the electricity.

“Instead, the electricity is resold into a wholesale market. The consumer continues to purchase electricity from the utility,” the report writers note, adding, “These contracts represent the majority of off-site renewable energy contracts signed by non-utilities in recent years.”

Why are virtual PPAs popular? One advantage is flexibility. Corporations can invest in projects with the best payback, not merely ones located close to the load that must be energized. These contracts also eliminate the complexity of having green power delivered to a corporate site, while offering a hedge against long-term price volatility in wholesale electricity rates.

NREL found that 43 percent of the 2,300 megawatts of utility-scale solar that corporations have signed up for through July 2017 fits within the financial or virtual PPA category, while 13 percent represents physical PPAs.

Looking ahead, industry participants think 2018 might be another busy year for PPA activity. That’s because corporate customers may rev up buying to take advantage of tax credits that are scheduled to begin phasing down in 2020. If the corporation buys into a solar project that begins construction before 2019, there’s still a 30 percent tax credit available to help pay for it.

Keeping utilities in the loop

Last September, the Las Vegas Sun reported on one whopper of a PPA. After a year-long battle, MGM Resorts International and Wynn Resorts won the right to part ways with NV Energy and begin purchasing power from another provider. NV Energy still provides backup and transmission, but it no longer sells power to the casino operators.

In losing those two customers, NV Energy lost approximately 6 percent of its customer base, the Sun article noted. To prevent ratepayers from paying the cost of this loss, regulators required MGM to pay some $87 million in impact fees, and Winn coughed up $15 million. Both organizations will also pay miscellaneous recurring charges for another five years.

That’s one way to help utilities avoid stranded assets, and researchers at Colorado State University’s Center for the New Energy Economy (CNEE) have some other ideas that might help utilities out.

Chief among those ideas is PPA tracking. CNEE researchers point to utility demand-management programs, which often have staffers who keep tabs on how much load an account might be able to curtail or shift. The CNEE team suggests that those account people or others gather similar information on PPA plans of these large accounts. Alternatively, utilities could conduct market potential studies.

Why create a mechanism to uncover, monitor and forecast corporate PPA plans? CNEE researchers say it could help utilities with their resource planning and thereby minimize the impact of corporate PPAs on other ratepayers. It also might help utilities identify where they could defer investments, and it could help regulators align C&I green-energy goals with public policy.

The CNEE team outlines pathways to plan for corporate renewable purchases in a paper titled Private Procurement, Public Benefit: Integrating Corporate Renewable Energy Purchases with Utility Resource Planning. It’s worth reading. After all, the researchers note, companies looking at PPAs represent some of the largest electricity consumers in the nation. “Their energy choices have a direct impact on utility resource needs,” the CNEE team says.